Last week, I woke up to my wife, who is black, sitting on the living room couch. She had trouble sleeping—not a rare occurrence, but this time was different. With streaks of dried tears, fading into her cheeks, she told me that she was simply “sad.” She was up for hours reeling from the recent murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor by cops and Ahmaud Arbery by white racist vigilantes. Compounding her grieving were the stories of the “Central Park Karen’s” intentional weaponizing of racism towards black birder, Christian Cooper, the disproportionately high rates of black people dying from Covid-19, and the cops’ repeated violence towards black protesters. The weight and trauma became unbearable. Micia was suffocating from the unjust and oppressive systems that repeatedly treats her and her people as less than and tells them that they are unworthy and expendable. My heart broke. I had never seen Micia like this. While these stories were nothing new to her, she’d had enough. She could no longer suppress the emotions, and something had to change.

I know Micia’s story (or some variation) has been typical for our black brothers and sisters all across the nation during this time, and I am grieving in solidarity with them. However, for all the anger, rage, frustration, and sadness I am feeling as a non-black person of color, it is nothing compared to what Micia and other black people are going through right now and forced to go through daily.

After holding Micia and being present with her and her pain, I asked how I could be most helpful. How could I use my experience and influence to support her in the moment? At Micia’s request, we co-created approaches and responses to advise her many white friends who have reached out with love and support and are seeking to take action to advance racial equity.

You have probably seen the many lists of resources and actions for white people being shared on social media. Where to start and what to do can be overwhelming and confusing. This blog post complements those lists—to provide insight on making your racial equity actions and growing ally-ship impactful and effective. Focusing on the why and how of your racial equity actions and overall journey will build a stable foundation from which to grow, take clear, strategic action, and achieve positive impact.

The following guidelines are not the end-all, be-all approaches that will guarantee efficacy, but they are foundational to help you get there. In the end, your degree of impact depends on you and your transformation. While most guideline content is tailored for white people at the beginning or middle stages of their racial equity journey, the guidelines may serve to re-ground change agents (white and BIPOC) as they continue to push for change.

6 GUIDELINES THAT WILL LEAD TO HIGHER IMPACT RACIAL EQUITY ACTIONS

1) Ask Yourself Why

Asking yourself why is a critical first step. Jumping straight to action without understanding “why and how” often leads to mistakes and ineffectiveness in racial equity work.

Ask, “why do I feel compelled to take action right now?” Repeat this question five times, forcing yourself to dig deeper each time. You have many daily choices on how to spend your time, and you are choosing this racial equity work now. Something deep inside is driving you. Explore where that is coming from and give voice to it. Write down your answers and re-visit them often. Messy or uncertain thoughts are okay. That will change over time. Your why will serve as your North Star—a place where you can recalibrate and re-ground yourself, especially when the work becomes really challenging—as you continue your racial equity journey.

(If you want to take a step further, ask, “why is racial equity important to me?” Then repeat the steps above.)

A word of caution: Be honest with yourself: if an answer was “to make myself feel better or more comfortable,” think carefully about what this means. For white people, this work is not about self-comfort, as explained in the Immerse in the Discomfort guideline below.

2) Center the Needs, Values, Voice, and Leadership of Black People

Centering black people may seem obvious, but I need to say it because white power and privilege run deep. Don’t rely on yourself to know or assume what black people want or need at this moment. A common mistake for white people, often white liberals, is to think they know what’s best for black people and to make critical decisions (large or small) that impact the black community, at times with damaging consequences. For example, an all-white leadership team decides what is best for their black and people of color staff. Or an all-white foundation staff decides what to fund and how much to fund when supporting the black community or, even worse, funds white-led organizations that are unintentionally or intentionally harming the black community. This white-centric approach is white privilege in practice and only causes more problems.

Properly centering black people will most likely lead to positive impact, yet how to do it effectively is challenging. The black community is directly impacted by systemic racism, so they are the best and only ones who can identify the most effective solutions that will benefit their community. Your job is to listen deeply to and follow the lead of black people and respond and support in solidarity. Support the advancement of their causes and goals as defined by the black community for the black community.

One way to center blackness is to reach out to your black friends (including close work colleagues) that you are close to and listen to their needs and priorities. BUT before you do so, ask yourself why you are reaching out. If it’s about you and making yourself feel better, don’t make contact. You are centering whiteness. If your black friend is an acquaintance, please don’t bother them. A thousand white people are trying to contact them right now. However, if you have a close relationship that includes mutual support and generosity with a black friend, reach out with empathy, curiosity, and humility. As you do, be gentle, sensitive, and understanding. Most black people are feeling raw right now. Remember, you reaching out is about them, not you. Understand that they may feel overburdened, overtaxed, overwhelmed, and feeling many emotions right now. Tell them you love them and are thinking about them. (If you are fearful of saying that you love them, then you may not have a deep enough relationship, so don’t reach out to them). Ask if it’s an okay time to talk. And if your black friend says they don’t want to talk, then leave them alone. Don’t be offended. Remember, this is about them, not you.

If they want to talk, ask questions with love, empathy, and compassion. Listen deeply. Talk little. Ask what you can do and do it. (Following through on recommended actions communicates you care deeply. Not following through may break trust and send the message that your friend and the black community are not important.)

If you don’t have any black friends that fit the criteria above, then go back to the first guideline and ask yourself “why” five times, then return here to explore other ways to understand the needs, challenges and priorities of the black community:

Reading, watching, attending, and listening to anything developed by black people, such as books, articles, films, events, or speeches. Learning about the priorities and values of black-led organizations that serve the black community. Reading online content from these organizations, subscribing to email lists, talking to representatives, and attending events.

Hiring a black racial equity consultant. Arguably, the best sources right now are black people who draw from both their lived and professional experiences to advance racial equity.

Attending racial equity trainings

Communicating with non-black people who are well versed in racial equity and are trusted by black people

A Word of Caution: Don’t expect black people to teach you. This practice actually centers whiteness and takes an emotional toll on the black person, potentially causing additional trauma or re-living past traumas. On the other hand, some black individuals don’t mind teaching (like Micia). Discover which of your friends are okay with this role. Lastly, some black people teach, train, coach, or consult professionally, so pay them and don’t extract free advice. You act like a white colonizer when you steal their knowledge.

3) Do it with Love

Numerous activists, such as MLK, Gandhi, and Jesus, embodied and spoke of love in their approaches. In 1 Corinthians 8 of the Bible, Paul states, “Love never fails,” which has been true in my racial equity work. When I have intentionally actualized love, I have been 100% effective—even when there have been temporary setbacks. These loving moments have led to many breakthroughs. We need a breakthrough moment right now, and we need your loving action for us to achieve it. Love in racial equity work is about seeing others, putting another’s needs above yourself, asking for forgiveness, forgiving those who hurt you, deep listening, and being empathetic, vulnerable, patient, kind, humble, generous, grateful, and soft-hearted.

Love pretty much guarantees success, but you must work at it. Heart work is hard work. Love is both an emotion and an action. As an action, love is about loving the receiver the way they desire to feel loved. I have had a huge learning curve on this approach in my marriage with the 5 Love Languages. In short, my love languages are not the ways Micia feels loved. To show my love, I need to spend quality time with her and provide acts of service (i.e., attack the honey-do-list). Since these loving actions do not come naturally to me, I need to work at them constantly.

You may think that stepping up for the black community at this time is in itself an act of love. However, there are nuances in how love may be manifested in actions that will lead to positive impact on the black community. For example, white people protesting in solidarity with black protesters is an act of love. It is a beautiful sight to see. However, white rioters who destroy property when black organizers ask them to stop is not loving and actually creates more problems for the black community who often receive backlash first and worst. Similarly, talking over a black person to defend them from an insensitive statement without their consent is not loving either. However, asking the black person with kindness, patience, and humility how you can best support them, following through on the recommendations, and checking back in is loving.

4) Immerse Yourself in Discomfort

Being uncomfortable in racial equity work means you are pushing into your growth edge and approaching the apex of your capability. If you are not feeling discomfort, then you are not doing enough. Discomfort is a good sign. It means you’re growing. A while back, during a J.E.D.I. training that I was leading, a white participant shared her goal—to be constantly uncomfortable for the entire four days, so she can learn and grow as much as possible. This experience jumpstarted her journey, and today, she has evolved into a strong white ally, continually making change in her sphere of influence.

On the other hand, while comfort could mean you are not doing enough, it could also mean you are protecting your white bubble of power and privilege, avoiding the real work and tough conversations about systemic racism and white guilt, fragility, and privilege. Be wary of remaining, slipping back into, or even protecting this state of complacency, which has had profound adverse effects on the black community. Rabbi Abraham Heschel, a civil rights activist, once said, “the opposite of good is not evil, the opposite of good is indifference.”

Being uncomfortable is also the least you can do to be in solidarity with black people. Because black people can’t avoid racism, they are constantly uncomfortable and stressed. Even if they wish to avoid and not think about racism, something will happen in their daily life that will tell them they are less than, such as being turned down for a job because they don’t “fit,” having to take extra precautions when driving, birding, or [insert activity] while black, or hearing about another black person being murdered by cops. These daily and constant traumas of racism are not only bad for their health; they are literally killing black people. Racism leads to increased cortisol levels that do not lower at night time (like their white counterparts), which leads to numerous health disparities, such as higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, infant mortality, and child asthma deaths than white people.

How can you stretch yourself to the point of discomfort in your racial equity work? Are you watching or reading material that is making you uncomfortable? Are you donating to black-led organizations to the point of feeling uneasy about the amount of money you gave? Are you constantly engaging in uncomfortable conversations? Are you uncomfortable admitting your implicit biases? Are you uncomfortable extending your love to the black community? Are you doing the uncomfortable and necessary work to achieve broad-scale change in your organization?

5) Commit to Personal Growth

Ongoing learning and personal development are necessary to achieve and grow your impact on a broader scale. To transform society, you must focus on transforming yourself. Mahatma Gandhi stated, “[o]ur greatest ability as humans is not to change the world; but to change ourselves.” The beautiful and empowering aspect of personal work is that you can decide to grow, learn, and change at any moment. You don’t have to wait for external factors. All you need is a conscious effort right now.

The most transformative moment in my racial equity work was attending a two-day dismantling racism training 15 years ago. The experience provided the real history of the U.S. that I never received in my schooling. I learned about institutional and systemic racism, how we are socialized to reinforce it, and our complicity (by simply not doing anything) in supporting racially oppressive systems. This uncomfortable and emotional experience shifted the very notion of how I understood the world and crystallized my racial equity lens. I saw systemic racism and its detrimental effects everywhere—in places and ways I just could not see before attending the training. The experience shaped my career trajectory and provided a strong foundation for my growth and increasing impact on the environmental movement.

During this time, many terms and ideas in the world of racial equity are being discussed, such as “diversity” and individual acts of racism, and you may feel overwhelmed by content overload. I strongly recommend focusing your personal growth on systemic racism since it’s a root cause of society’s racial problems. Learning how to identify and dismantle it and about your role in reinforcing and protecting it through white power, privilege, and fragility will go a long way toward advancing racial equity.

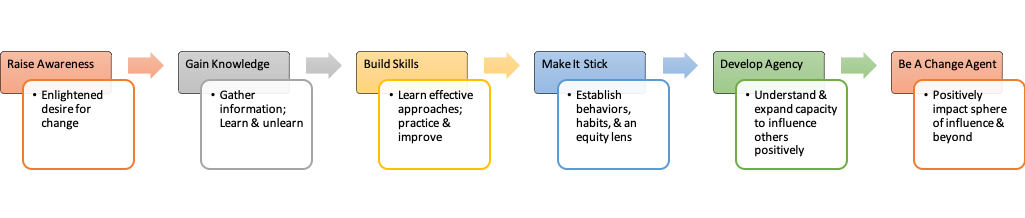

As you grow, think about the steps you may take. One way I support my clients is utilizing the following stages of development, in which you can self-identify and focus your work. (Your progress may be linear at first then circular, especially as you advance past the Gain Knowledge stage.):

As you can see, reading a book, while necessary for your development, will never be enough. What stage do you need to focus your work on right now? Do you need to increase your knowledge base by watching documentaries and attending trainings? Is it the right time to build skills, such as effectively communicating across differences and developing inclusive teams? Do you need to create consistent behaviors and habits, so racial equity work becomes second nature? Focus on one area for now and make a plan for your growth and development.

Words of caution: You will never be perfect at racial equity work (period). Do not allow perfectionism to paralyze you.

Stagnation is a common trait of problematic white people (often white liberals and self-proclaimed white allies). These white people believe their current understanding of race and racism and/or liberal values are sufficient. However, they are often stuck in the Raise Awareness or Gain Knowledge stages and have not built adequate skills, behaviors, and approaches to be effective change agents and white allies. They are not growing and often show no or minimal effort to do so. These white people often take up space, consciously, or subconsciously, utilizing their white power and privilege to block people of color and change agents from engaging in and more effectively advancing critical racial equity work. For example, this harmful trait is common in white executive directors and CEOs who often are not the most racially competent at their organization. Yet, they control in subtle or overt ways the direction of the organization’s racial equity work. They prevent the organization’s change agents from fully immersing in racial equity work, and in the end, the organization and people of color suffer.

6) Play the Long Game

Systems and institutions that protect, reinforce, and spread racism have been created and re-created since our nation’s founding and remain deeply ingrained in our culture and collective psyche. The work to dismantle all these racist systems and rebuild and maintain racially equitable systems is forever-work. If we each do our part over the long haul, we can make huge leaps towards racial equity.

Therefore, one-off actions, like reading a book or a one-time donation to Black Lives Matter, could be helpful but are grossly insufficient. All are important steps in your journey, but the real, impactful work occurs over time. For example, after writing this blog, I plan to check in with Micia to see what’s next, provide advice and build deeper relationships with over a dozen people who reached out to me, and strategize with a group of change agents in the environmental movement (defund mainstream environmentalism? Just sayin’). All this work is unpaid, but necessary, to advance racial equity in the way I can contribute.

Racial equity work is not a 100-yard sprint but an ultra-marathon, mostly up-hill. (This New Yorker cartoon humorously depicts the road ahead.) Your job is to build your stamina and strength and strip off the unnecessary weight. Focus on the process. The process is where growth and progress occur and results in more impactful outcomes. The process is the work.

As you continue on your journey, be kind and patient with yourself. Integrate self-care, so you don’t burn out. We need you for the long-haul. The more enduring and strong hands we have, the easier it will be to push the boulder of justice and equity up the mountain of systemic racism.

“We Shall Overcome”

I have intentionally been doing racial equity work for 20 years—47 years if you count my lifetime experience encountering racism. It’s been the most challenging, emotional, and rewarding work of my life. During this work, I have experienced some of the worst and some of the most beautiful moments of my life. I wouldn’t trade it for the world because, especially during this time, I can fully love the most important person in my life the way she needs to be loved. Waking up to Micia in her sadness and grief was one of the toughest moments of my life, and I am so grateful to her for letting me in and allowing me to swim in the messiness with her. It is in these times of deep sadness that deep love lives (and can grow). Our nation is currently experiencing a collective deep sadness, which doesn’t happen often. Search for the collective deep love. It lives. Uphold it, embody it, and put it into action. MLK once said, “[h]ate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.” Stay vigilant and intentional with love, and, as has been sung for centuries, from slaves to civil rights activists, “we shall overcome.”

Which guideline resonates most with you? Why? What are you inspired to do next? Why do you feel compelled to take action right now?

Appendix

These are the knowledge-building activities that Micia and I have recommended the most, during the past few weeks:

Attend a two-day racial equity training (This is a must-do if you are serious about racial equity work. Racial Equity Institute is an incredible black-led organization that provides these transformative trainings.)

Read White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard For White People To Talk About Racism by Robin D’Angelo

I am offering pro bono, 30-minute coaching sessions for people working in the environmental movement. Specifically, if you are a funder, staff leader, person of color, and/or J.E.D.I. point person, seeking advice, email me at marcelo@jediheart.com.

A special thank you to Micia Bonta, Sean Watts, and Mychal Tetteh who provided critical input and guidance for this blog post.